Just outside of our nation’s capital, amid Virginia’s rolling hills and picturesque stone walls, is a place that time seems to have forgotten, the place Sheila Johnson calls home.

She came here in 1996 to find refuge. At the time, BET (Black Entertainment Television), the company she and her then-husband Bob Johnson had co-founded, was hugely successful. But their struggling marriage was the talk of the town.

“The rumor mill was off the chart,” Johnson said. “People would tell me, ‘I saw them at the Super Bowl.’ ‘Oh, I saw her come down in his shirt.’ And I said, I need a place where I can be alone, at peace.”

CBS News

Today, Johnson is a very successful businesswoman, part owner of three sports teams (the Washington Mystics, Washington Wizards, and Washington Capitals), and the first Black woman to make it into the very exclusive, very white, and very male billionaire’s club. And yet, she said, tongues are still wagging. “You know, they look at me and they go, ‘Okay, you were so-called the first Black billionaire and everything, and you’ve had it so easy.’ No, I haven’t.”

“Do people say that, You’ve had it so easy?” asked Giles.

“You have no idea. There’s so many stories out there. They need to hear from me.”

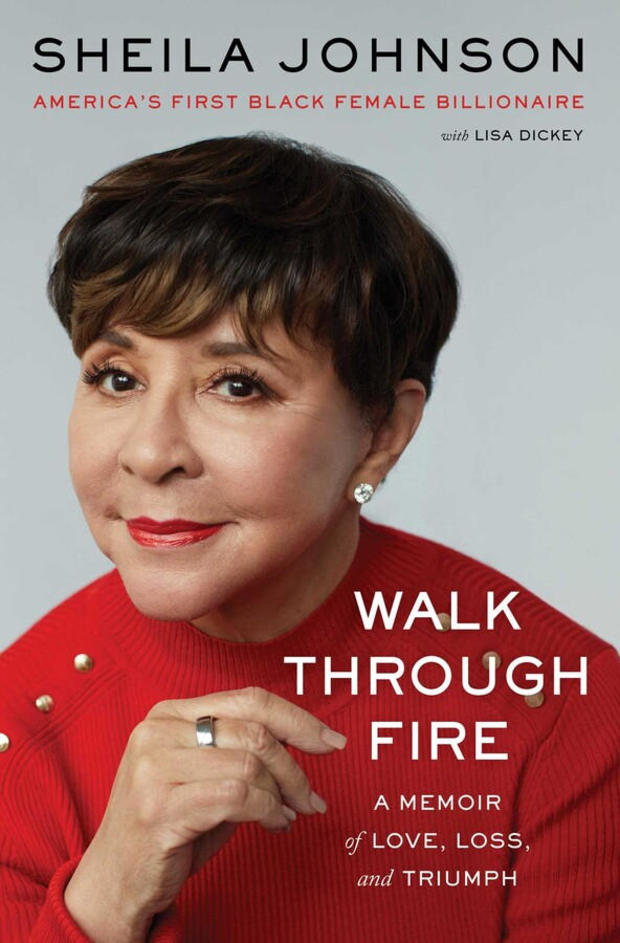

Her new book, “Walk Through Fire: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Triumph” (published by CBS’ sister company, Simon & Schuster), takes its title from the legend of the salamander. “It’s the only animal mythically that walks through fire and still comes out alive,” she said.

Simon & Schuster

It’s also the name of her impressive collection of five-star luxury resorts.

It’s been ten years since the doors of her flagship Salamander Resort & Spa in Middleburg, Virginia first opened. It was not, she admitted, an easy road.

In some ways, the town of Middleburg had welcomed her: “But the thing that really bothered me was driving into town every day and seeing a confederate flag in a gun shop,” Johnson said. “When I saw that flag, I said, God, where did I move to? And I just decided to buy the building. And it’s now a wonderful market. That’s the beauty of having a little money.”

Getting the town’s approval to build a resort was another matter. “I thought I had left one fire. I jumped into a great big one. And I forgot I was south of the Mason-Dixon Line. They came after me with all barrels. They signed petitions. We had hearings. I won by one vote.”

One thing to know about Sheila Johnson: Giving up is not in her DNA.

She credits the impact that her mother had on her: “Here she was at the top of the social circle, as a woman, as a mother, married to a doctor.”

Theirs was an African-American success story, though that success was hard-won. By the time she was ten, Sheila Crump had moved 13 times, owing to the work situations of her father: “We moved about every ten months,” she said, “’cause my father couldn’t practice in white hospitals. And he couldn’t even operate on white patients.”

Finally, her father got a permanent job in Chicago, and they were able to buy a house and settle down. Sheila took up the violin, and excelled at it.

And then, without warning, her father announced he was leaving the family. “It brought us all to our knees, because it was just one night, and he says, ‘I’m leaving.'”

Her mother had a breakdown. “She had always been my backbone,” Johnson said. “And I was losing her. It just really kind of destroyed me in a way. And then I realized, I said, Sheila, you know, you can’t play the victim here.”

With the help of her violin teacher, she got a music scholarship to the University of Illinois, where she met an upperclassman named Bob Johnson.

Sheila was young at the time. “Really young. How about 16-and-a-half?”

Her first impression of Bob Johnson? “I was always looking for someone with ambition,” she said. “But I was also going through something else psychologically, because my father had left. I felt unloved. He wanted me. And because of him wanting me, I wanted him.”

Their marriage lasted for 33 years. Today she says she shouldn’t have let it go on as long as it did. “I didn’t want to be a failure,” Johnson said. “And I kept saying, I can get through this. And I was really behind him. So much so that I got erased out of the picture.”

Their divorce was finalized in 2002. By coincidence or fate, the end of that chapter was the beginning of another. “As I walked into the courtroom, I looked at the judge, and I looked at my lawyer, I said, I think I know this guy.”

The “guy” was Judge William T. Newman Jr. He recalled: “Many, many years ago we happened to be in a play together. [Lonne Elder III’s “Ceremonies in Dark Old Men,” at the Washington Theater Club.] When the case was over, she said, ‘Excuse me, Your Honor, can I approach the bench?’ And I said, ‘Sure.'”

Johnson asked him, “‘Do you remember me?’ He goes, ‘Oh yes, I do!'”

She invited him to a gala she was hosting. She addressed the invitation, “William T. Newman Jr. and guest.”

Newman told his mother about it, suggesting he’d take someone he had just started to date: “My mother said, ‘Oh, no. You go to that party alone!'”

Three years later, Sheila and William married, in a lavish wedding that was the social event of the season. “I said, I love this man so much, we are going to celebrate,” Johnson said. “We had 750 people at that wedding. It was, I have to say, the most beautiful wedding.”

These days, Sheila Johnson is looking forward, not back. And she has no intention of slowing down: “I’ve come to reconcile the fact that we do need to walk through fire in order to come out stronger at the other end.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Lou Teel. Editor: Mike Levine.